For a number of years, Donald Trump has been tweeting about the myth of climate change based on cold weather. Just this past week, he even sarcastically called for more global warming. While most of people reading this essay will quickly dismiss Trump’s claims, it’s important to consider how our students think about not only climate change, but also the relationship between humanity and the environment in general. Most of the essays on Liberating Narratives focus on individuals or groups of peoples who have been marginalized in how we think about modern world history, but it’s just as important for us to keep in mind how much are we, as teachers of world history, integrating environmental topics into our courses in meaningful ways. In the last couple of years, there have been a number of short and engaging articles about the Little Ice Age that can be the basis for some great class discussions that really challenge students to think about the past (and the world today) in different ways.

The Fourteenth Century

In my class, I first talk about the Little Ice Age in connection to the Black Death. In Felipe Fernández-Armesto’s The World: A History, there is a useful chapter “The Revenge of Nature” in which he discusses the onset of cooler temperatures in conjunction with the Black Death in the fourteenth century. There is also a useful clip from the Millennium series, which Felipe Fernandez-Armesto wrote, that also shows the ways in which cooler temperatures made the consequences of the Black Death even worse and the ways in which it contributed to social upheavals in Europe. (If you don’t like history videos which include historical reenactments, don’t watch this!)

I only spend a few minutes discussing the topic, but by introducing the Little Ice Age into the course earlier, it helps students to start thinking about climate change as a historical process rather than as a topic that only gets debated about by politicians. There is also the recent The Great Transition: Climate, Disease and Society in the Late Medieval World by Bruce Campbell, a professor at The Queen’s University of Belfast, in which he makes important arguments about interconnections between climate change, the spread of the Black Death, and wars in Europe. Monica Green, has an excellent review of The Great Transition in which she discusses both the significance of his arguments and the limitations:

Campbell and Harper both suggest that the people of the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages were not simply the victims of ill fortune: they were human actors faced with the reality of climate change. Campbell has succeeded in making the Great Transition a historical turning point with which all narratives of European history must now reckon. If he has been less successful in the epidemiological parts of this investigation, that is because the methods of thinking globally in disease history are not yet as advanced as they are in the field of climate history. We are only now learning how to read genetic lineages as rough maps that show us both the geography and the chronology of evolving diseases.

Green also has added a few further thoughts about Campbell’s book on Twitter.

The Sixteenth Century

I then focus more on the Little Ice Age when students are discussing the consequences of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the Americas. We often focus on the Great Dying and the Columbian Exchange as the main global processes, so students are already thinking about large scale global processes and how humanity interacts with the environment. In recent years, there has been a lot of scholarship on the connections between the Little Ice Age and the Great Dying. In Ways of the World, Robert Strayer has a useful section on this topic, which is ideal for introducing the debate to students. There is also an excellent article “Did the Spanish Empire Change Earth’s Climate?” from Dagomar Degroot, a professor at Georgetown University, in which he brings together a lot of the recent scholarship on the relationship between Spanish conquests and policies in the Americas in the sixteenth century. The article is probably more than most students need, but it’s a useful reference for teachers or a good starting point for students who want to discuss the issue more.

This debate about the Spanish Empire, the Great Dying, and the Little Ice Age has just recently again showed up in the mainstream news. This past week, Jonathan Amos, a science correspondent for the BBC, published “America colonisation ‘cooled Earth’s climate'”. He discusses the recent “new” scholarship about population decline in the Americas and how it contributed to a drop in CO2 emissions. Dagomar Degroot quickly provided a few thoughts and criticisms of the article on Twitter. He highlights the wealth of scholarship on this topic and some of the problems with Amos’ article.

The Seventeenth Century

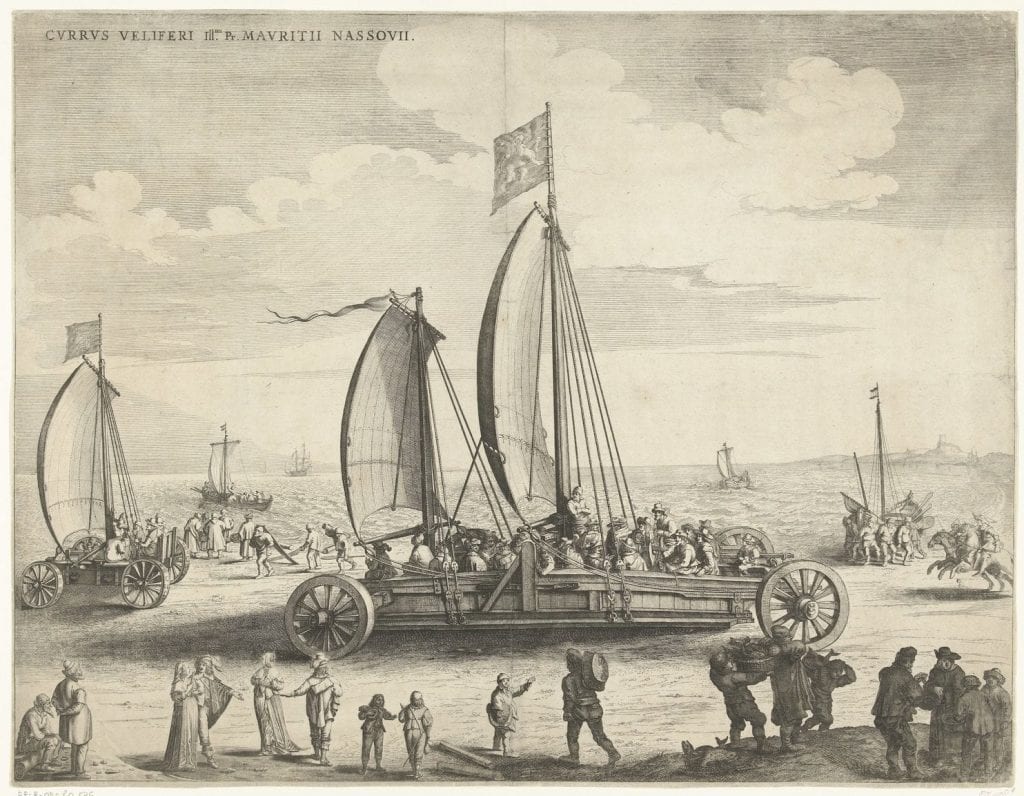

At the end of my unit on the Early Modern/Late Agrarian Period, I circle back to the Little Ice Age for a third time. I have students read Geoffrey Parker’s “Lessons From the Little Ice Age” and Dagomar Degroot’s “How the Dutch Prospered in the Little Ice Age.” Both articles are short and engaging summaries of recent books by the two authors. They also both focus on the seventeenth century and the Little Ice Age. Parker discusses the way in which cooler temperatures interacted with political and economic upheavals in the seventeenth century. Degroot discusses the way in which the Dutch were actually able to prosper in the seventeenth century, while many other societies around the world were struggling with the Little Ice Age and the General Crisis. By this point in the course, the students are already familiar with the Little Ice Age, so we are able to jump into the discussion. While the Parker article helps students to understand some important lessons about climate change for human societies, the Degroot article provides an important reminder about different places around the planet experienced climate change in different ways.

The Dutch developed the “sailing car” during the Little Ice Age.

Amitav Ghosh just recently published “The Coming Climate Crisis,” in which he discusses the scholarship of Parker and Degroot and connects the events of the Little Ice Age and the seventeenth century to our present-day problem of climate change. I know I’ll be integrating this article into my course next year. Another way you can approach the Little Ice Age in the seventeenth century is using the Crash Course episode “Climate Change, Chaos, and The Little Ice Age.” John Green draws on a lot of the same recent scholarship that I’ve been discussing in this essay, but he presents it in a more dynamic manner. The choice of which resources to use probably comes down to how you like to teach and the reading levels of your students (and how much you’re prepared for John Green’s intense and joking style).

Visualizing the Little Ice Age

Another way to approach the Little Ice Age in our classrooms is through paintings. While none of the artists at the time knew they were living in a period of climate change and cooler temperatures, they did see and experience the effects of that climate change on a daily basis. There is a useful new article published on The Artstor Blog that explores ways of “Picturing the Little Ice Age.” I found the image of the skating owls at the start of this post on the blog. And while the picture is simply cute, it also speaks to the reality of the cooler climate in the seventeenth century.

The Hunters in the Snow, also known as The Return of the Hunters, is a 1565 oil-on-wood painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. It is one of the more well known paintings related to the Little Ice Age.

Conclusion

Bringing the Little Ice Age into our classrooms for more than a few minutes is a great way to challenge students who may think of history as being limited to political events. It’s also a great topic for students who are more typically “math-and-science” or environmentally-minded students who are interested in climate change and climate justice. If you make use of a few of these resources, it’s also an exciting way for students to see how historians continually debate and reinterpret issues, the ways they make use of different types of sources, and how history is really about storytelling. Are we as historians telling inclusive stories?

The Little Ice Age affected the world from the fourteenth through the eighteenth centuries, but it heavily affected Northern Europe. During this period, Northern Europe was very much on the periphery of the larger global economy, and yet much of this scholarship focuses on the effects in Europe or in European colonies. If we’re better at telling stories about climate change in the past that engage “marginalized” peoples, how do we tell stories that show how climate change today affects different peoples in different ways? How are the stories about the past encouraging students to better understand and better challenge the stories they are now hearing about climate change and global warming? And to think about the broader goal of this site, how do we integrate the peoples of the Global South and indigenous peoples, the people that are too often marginalized in our news, into our understanding and discussion of climate change today in meaningful ways?

I also have put together Beyond Europe’s Cold Winters: Globalizing the Little Ice Age – a resource page which brings together some more resources related to the Little Ice Age with a focus on how it affected regions beyond Europe.